More Information

Submitted: July 02, 2024 | Approved: July 09, 2024 | Published: July 10, 2024

How to cite this article: Winn SP, Shyam T, Isabel Fiel M, Huang Y. Accessory Splenic Mass Masquerading as Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Arch Cancer Sci Ther. 2024; 8(1): 037-040. https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.acst.1001042

DOI: 10.29328/journal.acst.1001042

Copyright License: © 2024 Winn SP, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Accessory spleen; Hepatoma, Hepatocellular carcinoma; Right diaphragm mass

Accessory Splenic Mass Masquerading as Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Diagnostic Dilemma

Soe P Winn1*, Tharun Shyam1, M Isabel Fiel2 and Yiwu Huang3

1Department of Internal Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

2Department of Pathology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, NY, USA

3Department of Hematology-oncology, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Soe P Winn, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA, Email: [email protected]

The spleen plays a pivotal role in our immune system by facilitating the proliferation and differentiation of lymphocytes and monocytes. Typically located in the left upper quadrant retroperitoneally, splenic tissue found outside of its usual position is termed ectopic spleen. When the tissue maintains its histological architecture and encapsulation and receives blood supply from splanchnic vessels, it is called an accessory spleen. Although it commonly presents near the splenic hilum or pancreatic tail, rare instances have been reported in the gastric, liver, gastrosplenic/lienorenal ligaments, as well as thoracic and gonadal regions. However, the case of an accessory spleen, mimicking a hepatic lesion in the right diaphragm represents a novel observation.

Accessory spleen, also referred to as polysplenia or splenunculus is a condition in which an additional spleen forms separately from the primary spleen due to congenital maldevelopment during embryogenesis. It is estimated that nearly 10% - 30% of the total population possesses an accessory spleen, and the median diameter of the accessory spleen ranges from 2 mm to 3.5 cm [1-3].

Development of the primordial spleen commences from the splanchnic mesoderm during the 5th week of gestation. This condition is postulated to occur due to either the failure of embryonic splenic tissue to unite in the dorsal mesogastrium or the detachment of tissue from the main spleen due to extreme lobulation during embryonic development. Additionally, abnormal rotation of the stomach and migration of the dorsal mesogastrium during the 7th and 8th week of embryogenesis may contribute to this condition. The most common location of an accessory spleen can be found in the hilum of the spleen, pancreas, gastrosplenic ligament, lienorenal ligament, and greater omental areas [1,4,5]. Herein, we would like to present a rare presentation of an accessory spleen located at the right diaphragm mimicking a hepatoma lesion, found incidentally in a healthy 39-year-old adult with no significant past medical history.

A 39-year-old male patient, with no significant past medical history, presented to the hospital due to an incidental finding of a liver mass during a work-up for hematuria. Although recently diagnosed with hypertension, he discontinued his antihypertensive medications after a week. He has no past history of hepatitis B or C infection, past surgical interventions, or known drug allergies. He does not take any medications. Socially, he is married, a non-smoker, and abstains from alcohol. His family history reveals no cancer or liver-related issues in his parents and immediate relatives living in China.

On physical examination, his vital were mostly within normal limits except mild elevation of blood pressure of 139/92 mmHg. His cardiac, chest, and abdominal examinations have been unrevealing so far. There is no skin rash, abnormal swelling, or edema detected throughout his body.

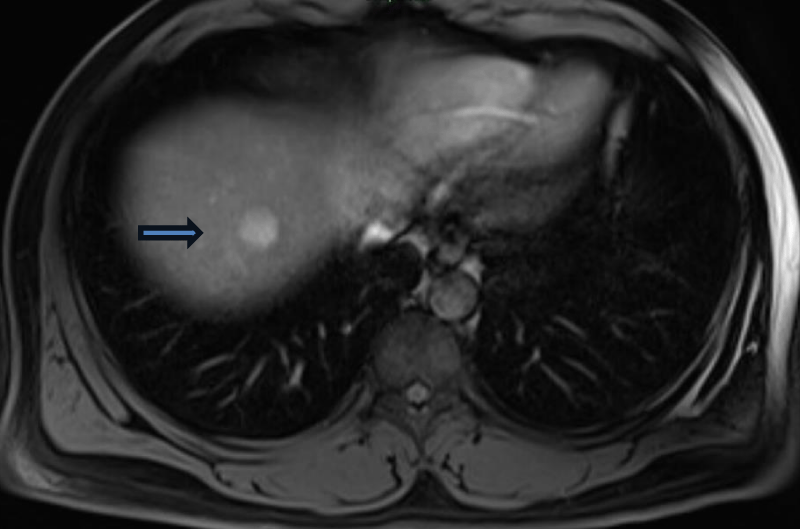

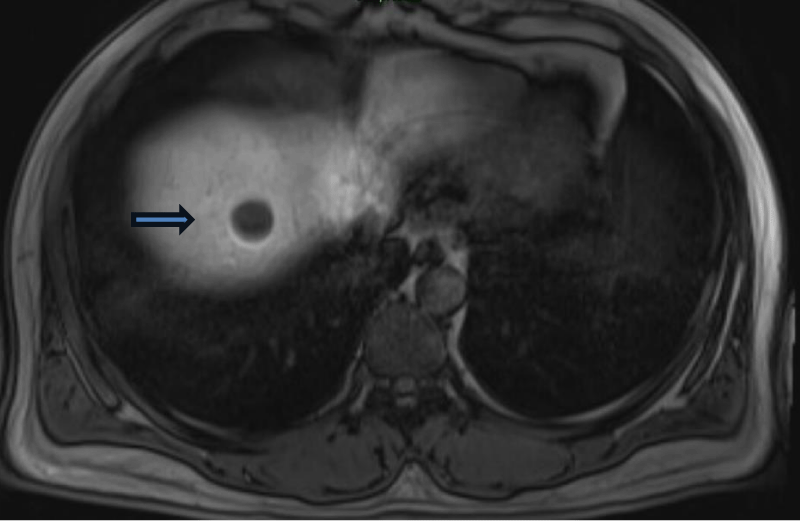

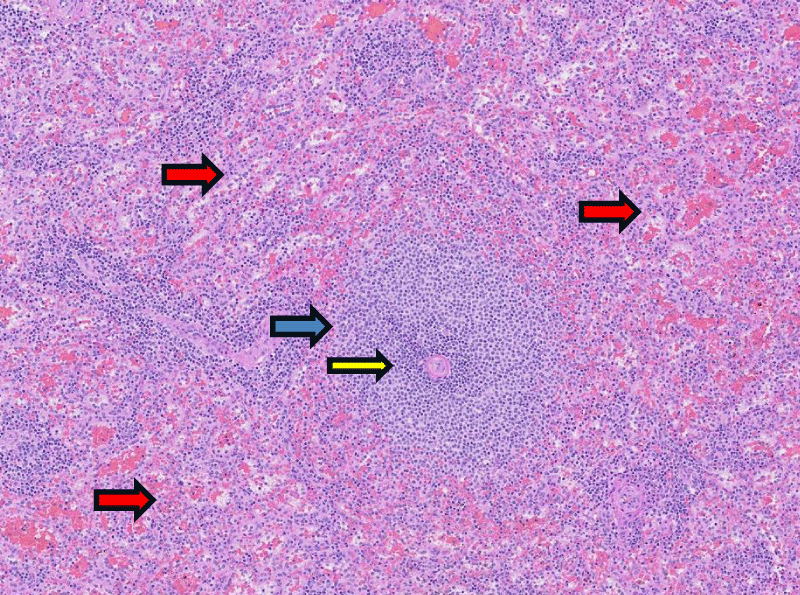

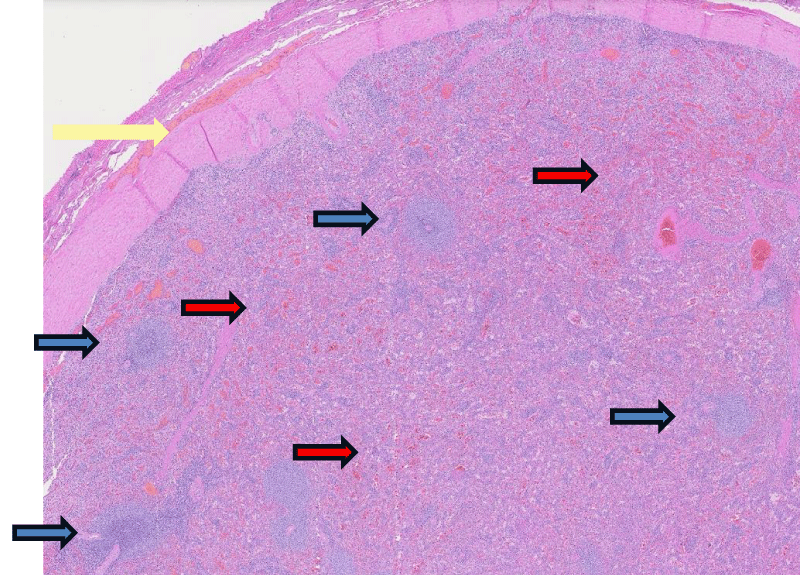

Routine laboratory investigations including Complete Blood Counts (CBC), basic Metabolic Panel (BMP), Liver Functional Test (LFT), coagulation studies, and hepatitis viral panels were unremarkable as well as the tumor markers such as Alpha-Feto Protein (AFP), and Chorionic Embryogenic Antigen (CEA). Further investigations followed a visit to his urologist for his hematuria and prescribed antibiotics for possible urinary tract infection together with an order for a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. The result revealed a 2-cm enhancing lesion in the right hepatic dome with moderate hepatomegaly and hepatic steatosis, which finding was recommended to repeat with an MRI scan. The patient returned to his primary care doctor and received an MRI scan as requested. MRI scan result revealed a 2.3 cm right hepatic dome lesion that showed signal intensity on the T2 weighted image with heterogenous enhancement on the arterial phase and persistent enhancement on the venous phase. An additional 0.5cm lesion was found in segment 6 of the right hepatic lobe, showing both arterial and venous enhancement. Both of these lesions concluded as indeterminate in pathology and was recommended another MRI scan with gadoxetate disodium for better characterization of liver lesions. It unveiled a mildly T2 hyperintense 2 x 2 cm arterial enhancing mass in the right hepatic lobe showing washout at the venous phase and absent contrast uptake in the hepatobiliary phase with restricted diffusion pattern, concerning malignancy (Figures 1,2). Additionally, a 0.7cm lesion in segment 6 of the liver was identified as a benign Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH) or arterial portal shunt. Due to the concern for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), the patient was referred to the Intervention Radiologist (IR) for biopsy after discussing the case and having consensus at the Hepatobiliary tumor board. The IR procedure was unsuccessful after finding it difficult to identify the mass during the ultrasound-guided biopsy procedure, which led to a laparoscopic resection of the mass. He underwent laparoscopic resection of the right diaphragmatic mass and mesh repair of the diaphragm defect as the mass was found to be distinct from the liver and attached to the right diaphragm during surgery. The surgical pathology revealed mature encapsulated splenic tissue with white and red pulps, confirming the diagnosis of accessory spleen (Figures 3,4). He tolerated the procedure well without any complications. On a follow-up visit to the clinic, he was doing well with minimal tenderness at the surgery site.

Figure 1: MRI of the liver in transverse section showing enhancing mass (blue arrow) during arterial phase.

Figure 2: MRI of the liver in the transverse section showing the same mass (blue arrow) manifesting washout phenomena during the venous phase.

Figure 3: Splenic tissue histology at the medium power (40x) showing white pulp (blue arrow) surrounding a central arteriole (yellow arrow) and red pulps (red arrow) at peripherals.

Figure 4: Splenic tissue histology at the low power(20x) demonstrating white pulps (blue arrow) and surrounding red pulps (red arrow) with splenic capsule (yellow arrow) encapsulating the bulk of splenic parenchyma the top of the figure.

From our literature review, the case of an accessory spleen located in the right diaphragm, mimicking a Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) appears to be the first of its kind reported. The diaphragm originates from multiple embryogenic sources, including the septum transversum, a mesodermal sheet, that initially separates the thorax and abdomen during early embryogenic development [6]. We hypothesize that our patient’s accessory spleen, also of mesodermal origin, may have migrated to the right hemidiaphragm due to anomalies during extreme lobulation of the primordial spleen in embryogenesis. However, the precise mechanism by which the accessory spleen in our patient’s right diaphragm occurred remains unknown.

Accessory spleens are typically incidental findings during radiological examinations conducted for other medical reasons and generally do not cause symptoms or complications. However, in some cases, they can lead to acute complications such as rupture due to trauma or torsion resulting in infarction [7-9]. Accessory spleen may also take over the role and responsibility of a normal spleen in individuals who have undergone splenectomy, as it possesses similar histological architecture and functional capacity. Therefore, in cases where diseases such as immune thrombocytopenia, or hereditary spherocytosis, recur or remain uncontrolled after splenectomy, the presence of a possible functioning accessory spleen elsewhere in the body should be considered [10].

This kind of scenario is not possible in the case of splenosis, which develops from a traumatic injury or prior surgery to the spleen and migrates to the other parts of the body, whereas the accessory spleen arises from anomalies during embryogenesis. Furthermore, an accessory spleen maintains its blood supply from its mother splanchnic blood vessels with preserved normal splenic architecture and a complete capsule, whereas splenosis acquires its blood supply from local blood vessels, with distorted or incomplete splenic architecture [11]. In our patient, the biopsy results revealed an encapsulated mature splenic tissue confirming the accessory spleen.

As a CT scan is the most common imaging modality in clinical practice, we should be aware of the typical findings of the accessory spleen, as it can mimic lymphadenopathy or malignancy if detected in other organs. According to Angarita, et al. the sensitivity of a CT scan for detecting an accessory spleen is 60% and the specificity is 95.6% [10]. Most accessory spleens exhibit homogeneous enhancement, with similar attenuation as the main spleen during contrast CT imaging, and typically display characteristic rounded, separate margins [2,12]. However, distinguishing these lesions from cancerous origins in most clinical settings proves challenging due to their small size, approximately 2cm, and their particular location within organs such as the liver or the pancreas. Differentiating them from HCC, the neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas or metastatic cancer is particularly difficult [3,13]. Consequently, this often results in unnecessary biopsies and excision of the lesions.

While histopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosis of an accessory spleen, it necessitates unnecessary excision or biopsy of the lesions. Currently, the preferred non-invasive tests involve functional scans, including Tc-99m-labeled Heat-Denatured Red Blood Cells (HRBC), and Tc-99m sulfur colloid scans. However, these scans require specialized expertise & facility and are not widely available like CT scans [13-15]. In our patient, concern over HCC persisted after an MRI scan with gadoxetate disodium (Eovist), which showed arterial enhancement with washout phenomena in the venous phase as seen in HCC. Repeated imaging studies failed to accurately diagnose the lesion pre-operatively, ultimately resulting in laparoscopic removal of the accessory spleen.

In summary, our case underscores the diagnostic challenge posed by the accessory spleen in the atypical sites such as the right diaphragm as observed in our patient. Despite advancements in imaging modalities such as MRI scans with Eovist, distinguishing accessory spleens from cancerous lesions remains a diagnostic challenge. Moving forward, heightened clinical suspicion and diagnostic awareness among clinicians and radiologists regarding the typical imaging features of accessory spleens are imperative to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgical interventions. This involves interdisciplinary collaboration and when necessary, the utilization of advanced imaging techniques to facilitate accurate diagnosis, especially in young individuals with low risks for cancer.

Ethics statement

The authors declared they retain informed consent from the patient and approval from the head of the department to publish.

- Wadham BM, Adams PB, Johnson MA. Incidence and location of accessory spleens. N Engl J Med. 1981 30;304(18):1111. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7207579/

- Rashid SA. Accessory Spleen: Prevalence and Multidetector CT Appearance. Malays J Med Sci. 2014;21(4):18-23. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25977617/

- Rodriguez E, Netto G, Li QK. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen: a case report and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41(5):466-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22241738/

- Halpert B, Gyorkey F. Lesions observed in accessory spleens of 311 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 1959;32(2):165-8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13670140/

- Grilli G, Pastore V, Bertozzi V, Cintoli AN, Perfetto F, Nobili M, et al. A Rare Case of Spontaneous Hemorrhage in a Giant Accessory Spleen in a Child. Case Rep Pediatr. 2019;2019:1597527. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30805239/

- Merrell AJ, Kardon G. Development of the diaphragm -- a skeletal muscle essential for mammalian respiration. FEBS J. 2013;280(17):4026-35. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23586979/

- Hems TE, Bellringer JF. Torsion of an accessory spleen in an elderly patient. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(780):838-9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2099424/

- Ozeki M, Asakuma M, Go N, Ogura T, Inoue Y, Shimizu T, et al. Torsion of an accessory spleen: a rare case preoperatively diagnosed and cured by single-port surgery. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1(1):100. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26943424/

- Leon L, Labropoulos N, Hudlin CI, Macbeth AG, Matolo N, Andrus C. Accessory spleen rupture in a patient with previous traumatic splenectomy. J Trauma. 2006;60(4):901-3. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16612318/

- García Angarita F, Sanjuanbenito Dehesa A. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen: a rare cause of recurrence of immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4(10):979-981. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27761250/

- Bajwa SA, Kasi A. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Accessory Spleen. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024; 30085582. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30085582/

- Mortelé KJ, Mortelé B, Silverman SG. CT features of the accessory spleen. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004 Dec;183(6):1653-7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831653. Erratum in: AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):348. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15547205/

- M S P, Matthew C, Rajendran RR. Accessory Spleen Mimicking an Intrahepatic Neoplasm: A Rare Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39185. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37332428/

- Stephenson RR, Amyes E, McKay G, Lalloo ST. Preoperative angioembolisation of a mediastinal accessory ectopic spleen: A case report and review of the literature. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17(7):2519-2524. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35601383/

- Weiand G, Mangold G. Accessory spleen in the pancreatic tail -- a neglected entity? A contribution to embryology, topography and pathology of ectopic splenic tissue. Chirurg. 2003;74(12):1170-7. German. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14673541/